Photo Credit: Thanksgiving family at dinner. No date on the image, but based on the hairstyle and clothes, I’m guessing this is probably around the 1880s or early1890s: Linnaea Mallette/Public Domain Pictures/CC0 1.0

Today is Thanksgiving in the United States. Thanksgiving is traditionally a time of gratitude and giving and many people have a big dinner with “all the trimmings” where both family and non-family members are invited. Although my family isn’t US-born, my parents adopted the Thanksgiving traditions and my mom always had a huge turkey and many of the trimmings (somehow, the sweet potato casserole with marshmallows was always missing…) and we always enjoyed it as a family.

The Waxwood series is set in the Gilded Age, which took place roughly in the last quarter of the 19th century. The series involves a wealthy Nob Hill family. How would the Alderdices celebrate Thanksgiving? Did they celebrate it at all?

Gilded Age aristocracy did indeed celebrate Thanksgiving but not the way we do now. For many of us in the 21st century, Thanksgiving means a large table crowded with food, fall colored table settings, lots of kids and grandparents and aunts and uncles. Rosy cheeks, laughter and family jokes abound. Our vision of Thanksgiving is like something out of a Norman Rockwell illustration.

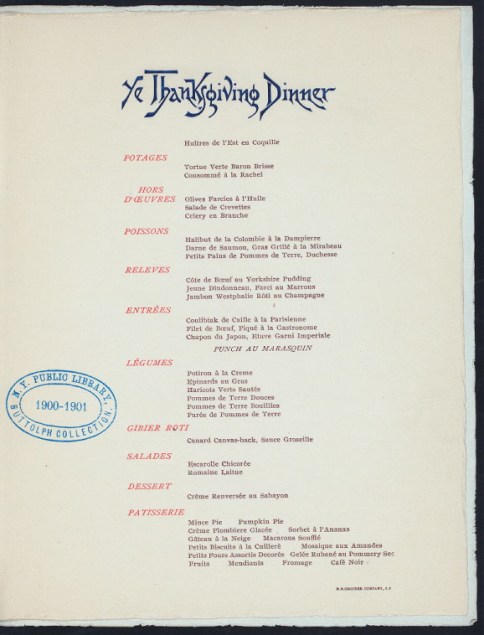

Photo Credit: “Thanksgiving dinner, Occidental Hotel, San Francisco, CA, 1891, scan by New York Public Library: Fee/Wikimedia Commons/PD scan (PD US expired)

But the aristocrats of the Gilded Age weren’t quite so committed to the idea of a family Thanksgiving. In fact, Gilded Age swells didn’t stay at home — they dined at the fanciest restaurants or hotel dining rooms. It was not unusual for Gilded Agers to feast on non-traditional Thanksgiving fair such as oysters, turtle soup, foie gras, prime rib, and Petit fours. The Thanksgiving menu at the Occidental Hotel in San Francisco (one of the swankiest of its day) hardly looks like the usual turkey with cranberry sauce, mashed potatoes, and pumpkin pie most Americans feast on nowadays.

We might be led to believe wealthy Gilded Agers weren’t as family-oriented as we are today, but as I pointed out in my blog post about the Gilded Age, people in this period in American history were obsessed with excess and an “over-the-top” feasting on life, especially those who could afford it. A family dinner at home simply didn’t fit in with their lifestyle. An extraordinary dinner at a fine hotel did, and many Gilded Agers used it as an excuse to show off their wealth and affluence with lavish clothes and jewelry. Many went to see and be seen.

If that sounds petty, keep in mind the concept of a family Thanksgiving was foreign to the Pilgrims as well. Pilgrims in the 17th century celebrated Thanksgiving with their neighbors and friends, often times without members of their families present, as many stayed behind in England or perished on the journey to America. Historians cite the 1920s Prohibition era and the Great Depression that follows as reasons why elaborate Thanksgiving festivities of the Gilded Age fell out of favor. That might be, but I’m guessing it had more to do with the post-World War II era when the family became more precious and important to Americans. This is why Rockwell’s illustration became so much a part of the American psyche and Thanksgiving associated with an intimate portrait of family.

Book 1 of the Waxwood Series, The Specter, gives the reader a taste of Thanksgiving in the 19th century. The holiday takes place in April, not November. In fact, until Franklin Roosevelt signed a proclamation making the third Thursday of November the official Thanksgiving holiday, you could find the day of thanksgiving during several different times of the year depending upon the state. If you’re curious, you can read more about that here.

The Waxwood Series has just gotten a make-over! To find out more about the series, this page will give you all the details.

Is the life of a Gilded Age debutante all parties and flirtations? Read “The Rose Debutante” to find out! It’s FREE! Plus, you’ll get to know about life in the past and about the resilient women the history books forgot. And how about fun historical facts, great deals on historical fiction books, and a cool monthly freebie thrown in just because? Here’s where you can sign up.