Photo Credit: The Librarian, Guiseppe Arcimboldo, 1570, oil on canvas, Skokloster Castle, Lake Malaren, Sweden: Armbrust/Wikimedia Commons/PD US

August 9 is Book Lover’s Day. As an avid reader and writer, books are as essential to me as breathing. Books were my dreamworld, my refuge from an emotionally difficult childhood.

This Book Lover’s Day, I decided to make a confession to my readers here. I am not like many authors who read voraciously in their genre. I hardly ever read books written by contemporary authors. I don’t mean contemporary literature, which you might expect of a historical fiction author. I mean books written by contemporary authors, even historical fiction. Most of my reading is classic literature, books written fifty or one hundred years ago or more.

Part of my upbringing involved people who lived in their own fantasy worlds. That, combined with my highly sensitive nature made me developed my own dreams and fantasies. My psychological reality growing up was an isolated childhood couched in strangeness and trauma, and my way of dealing with it was to live outside of reality as much as I could with daydreams, journaling, and writing. I was never out of touch with reality (neither were my parents). I just preferred this fantasy world I had built for myself, which was my safe, happy world. A large part of that world came in books I read. Books gave me an escape into a world far more controllable than mine was.

While I was always a dreamer in love with the fantasy world of books, it wasn’t always true that I was in love with classic literature. As a teenager, I read the classics only when they were assigned at school. My leisure reading was contemporary to my time. But when I entered college, I discovered an entirely new world. As an English major, I was exposed to what is known as the “literary canon” from the birth of English literature to modern times. I read the likes of Dante, Dickens, Bronte (all three of them), and Fitzgerald, among many others, for the first time in my life, and I learned about all the important literary movements, like Romanticism and Modernism. I lived in these books, in the world of the characters, far removed from what I had ever experienced as “real life”. They took me into another time as well as another place, where I could rest my imagination. Most English students hate literary analysis and a colleague of mine once complained that learning how to analyze a literary text made her stop enjoying the books she read. But for me, literary analysis taught me to pick apart language, characters, and themes, so that I saw how relevant the passions and pains of, say, an Anna Karenina or a Daisy Miller were to me, even though my life was so different from theirs.

After college and after grad school (again, in English, so I got to read even more classic texts), I continued to read these books. My Kindle app is probably about 90% classic fiction. Some of the authors are well-known but others are more obscure, such as Gertrude Atherton, Anais Nin, and Jane Bowles.

Last year, when I started to work on my Waxwood Series, I made an attempt to read historical fiction written by contemporary authors. I did this mainly because I wanted to see what other authors were doing and the old adage given to authors of “read in your genre” was making me feel guilty for not having sought more of these authors before. The majority of books that I started to read I would put down at some point. It had absolutely nothing to do with the authors or the quality of the books. It had to do with my personal comfort zone. Reading is so necessary to my psyche that trying to read these books, which made me feel like a fish out of water, I felt as if I were slogging through a field thick with tall wheat without a sickle. There were a few I enjoyed with, such as Anna Hope’s The Ballroom and Gregory Harris’ The Endicott Evil but the majority of these books just didn’t speak to me. I wish I could tell you why.

So after a long, hard struggle with myself after a year, I realized I am just not going to enjoy reading if it feels like a chore. So I’m now back to my beloved classics.

I’ve discovered beyond enjoyment there are also practical benefits to reading the classics. These books prepare me better for writing historical fiction because they put me inside the language and everyday life of the past as well as give me windows into the attitudes, morals, and mentality of the people living at that time. There is no denying that the rhythms of the past are very different from the present (as they should be) and it’s very difficult for historical authors writing today (myself at the top of the list) to capture those nuances. Reading classic fiction puts me in this mindset.

These books are also a surprising source of information for me, sometimes better than all the research books I can find. For example, it’s been very difficult to find a lot of information on the aristocracy of San Francisco in the Gilded Age, a major component of the Alderdice family in my Waxwood Series. While there is a lot out there about this distinct class during this period of American history, most books and articles focus on those who lived on the East Coast, like New York City and Boston. But much of the research I’ve found seems to neglect the West Coast aristocracy in this time. However, I discovered a wonderful writer who wrote many of her books about this class in San Francisco and the Bay Area in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries —Gertrude Atherton. Her detailed discussions of the rise of the aristocracy in San Francisco in the mid-19th century in one of her more well-known books, The Californians, gave me a lot of information I couldn’t find anywhere else that helped shape the Alderdice family past and present. A few of her other books that tackle this society in the Gilded Age and at the turn of the century have also been very helpful to me.

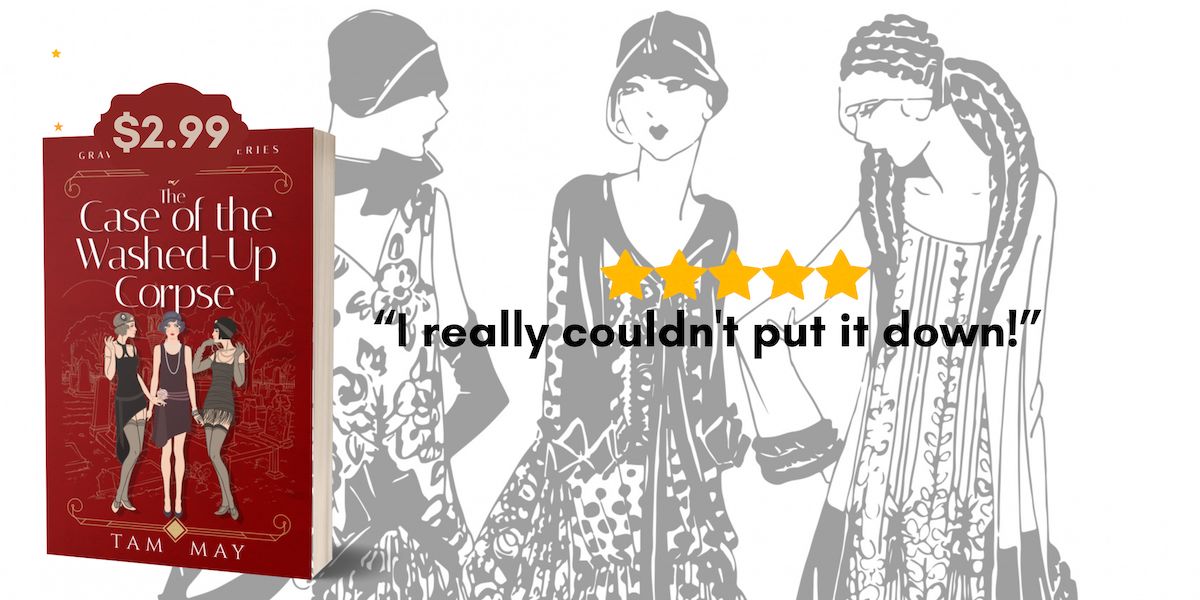

To find out more about the Waxwood Series, you can go to this page. Book 1 of the series, The Specter, is out and you can find out about that here. Book 2 is now in the works and set to be released in December of this year, so here’s the information about that.