Photo Credit: Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, the godmothers of the women’s suffragist movement, in the Gilded Age, 1891, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division: Taterian/Wikimedia Commons/PD US expired

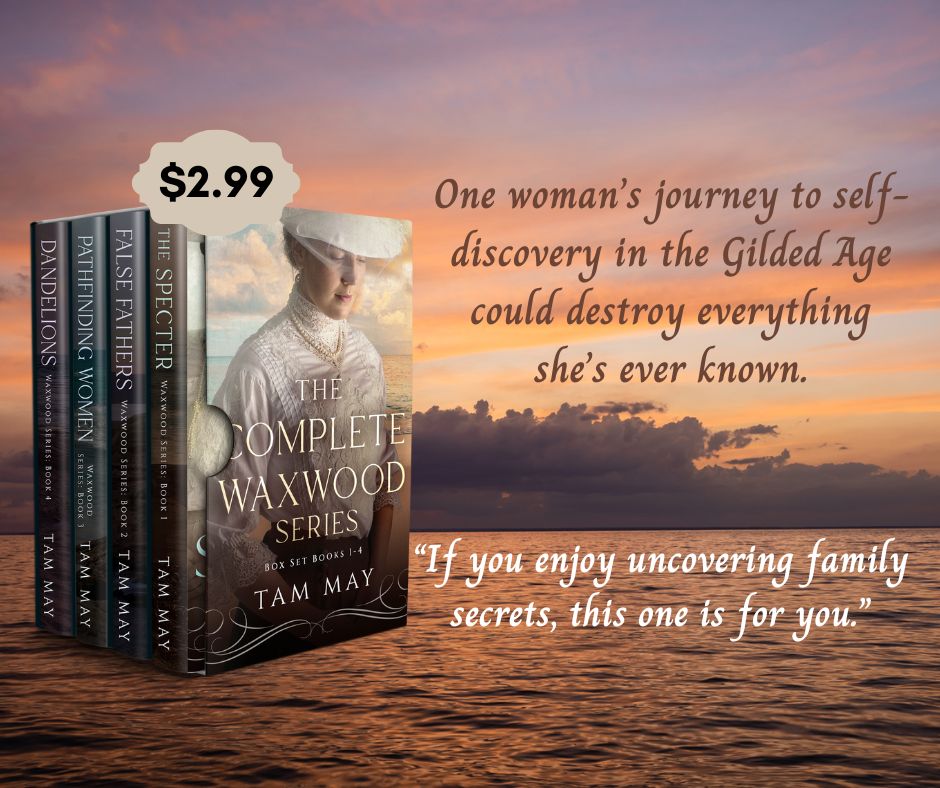

Last week, on August 18, to be exact, was the 99th anniversary of the day that the 19th amendment (giving women the right to vote) was ratified in America. I have written many times in my blog posts about the fact that women’s social and psychological position in history is of paramount interest to me and plays a role often in my fiction. This is true of The Specter, the first book of my Waxwood Series. I talk more about that in my blog post about why I write women’s fiction.

So in honor of the day, I thought I’d look into women’s suffragism in America in the 19th and early 20th centuries, before the amendment was ratified, which was in 1920. First, we must distinguish between women’s suffragism and women’s rights, because they are actually not the same thing. The former refers only to the political right for women to vote. The latter, on the other hand, is a broader term that encompasses more specific political, social, economical, and psychological aspects of women’s freedom to act and be. Once women got the right to vote, women’s suffragism was no longer necessary, but the fight for other rights for women was and still is.

Why were women so concerned about getting the right to vote in the 19th century? Actually, they weren’t — no at the beginning, that is. By the “beginning”, I mean the 1840’s when the idea of women’s suffrage was first formed. The Seneca Falls Convention is generally considered the birth of the women’s suffragist movement and for good reason. It was the first time women organized to discuss their rights and make decisions as to what they wanted to accomplish in their efforts to ensure women were seen and treated as free and equal beings. The convention participants made eleven resolutions to this effect, all of which you can read fully here. What is interesting to me is that these resolutions keep within the framework of the separate spheres. Women were expected to remain in the private sphere, that is in the home and church, perceived as “angels in the house” — virtuous, morally superior to men, and too fragile to handle the dog-eat-dog world of the public sphere. The majority of resolutions don’t challenge this perception and in fact ask for equal and respectful treatment of women in their own sphere. There is one exception — Resolution #9, which declares the right of women to vote. Not surprisingly, this was the only resolution to stirred up controversy and was not voted unanimously by the participants. It may have been that the idea of women having a voice in the public sphere was too revolutionary to consider at that time.

However, in the Gilded Age, the idea of women having the vote started to become feasible in the minds of many women suffragists. Women’s political organizations began to form in the 1870’s specifically geared toward pushing government to pass an amendment allowing women to vote. Several women, including Susan B. Anthony, one of the godmothers of the Seneca Falls Convention, boldly went to the polls to vote and were turned away. Anthony succeeded in voting and was arrested for doing so. Women filed lawsuits but the Supreme Court ruled in 1875 to reject women’s suffragism as a right, claiming that the constitution does not grant suffragism to any group, including women.

Women suffragism had many detractors, both male and female, and caricatures abounded in the papers. Here’s one where the supposed horrific consequences of giving women the vote is depicted, with women lining up to vote for the “Celebrated Man Tamer” while the harassed-looking man at the end of the line has a baby thrust in his arms to allow his wife to vote.

Photo Credit: The age of brass. Or the triumphs of women’s rights, Currier & Ives, 1869, lithograph, New York: Churchh/Wikimedia Commons/PD US

After this failure, women suffragist groups took a different tactic, one that is distinctly American. They figured that if they could lobby individual state legislators so that laws were passed granting women the vote in individual states, the federal government would soon follow. They were right, though it took about forty years. But by 1920, when the 19th amendment was ratified, according to the U.S map here, about three-quarters of the states had either granted full voting rights to women or partial voting rights.

Many of us have heard of the guerrilla tactics used by women suffragists in Great Britain which were dramatized in the 2015 film Suffragette. Interestingly, American suffragists used less militant tactics to reach their goal. They mainly lobbied, petitioned, and picketed. This is not to say some didn’t experience their fair share of violence, though. One infamous example is the 1917 Night of Terror, where women’s picketing the White House led to torture and violence when they were jailed. However, a year later, the courts ruled that jailing suffragists was unconstitutional, and, two years later, women in all states in the nation gained full voting rights.

Women suffragism doesn’t play a big role in terms of the political stage in the Waxwood Series, though there are certainly stirrings of it. A minor character in the series, a wealthy widow named Marvina Moore, befriends Vivian and becomes a supporter of suffragism, educating Vivian as the series progresses. In my upcoming historical mystery series, The Paper Chase Mysteries, women’s suffragism plays a more active role in Adele’s character, especially her views on the more militant aspects of the movement.

To learn more about The Specter and order a copy, go here. To learn more about the Waxwood Series, you can take a look at this page on my website. If you like mysteries and are interested in finding out more about The Paper Chase Mysteries, you can do so here.