When I first conceived the idea of the Adele Gossling Mysteries, I wanted to know what life was like in the first years of the early 20th century. I knew my first book, The Carnation Murder, was going to involve an aristocratic family, so I went in search of anything (books, movies, etc) that portrayed life among the aristocracy. I stumbled upon a series that, although it takes place in Britain, mirrors the life wealthy Americans would have lived during this time. I immediately fell in love with it.

Photo Credit: Jean Marsh, who co-created and starred in Upstairs, Downstairs at a signing at the Broadway Theater in Barking, East London, cropped, 12 December 2009, taken by Tim Drury: Rhain/Wikimedia Commons/CC BY SA 2.0

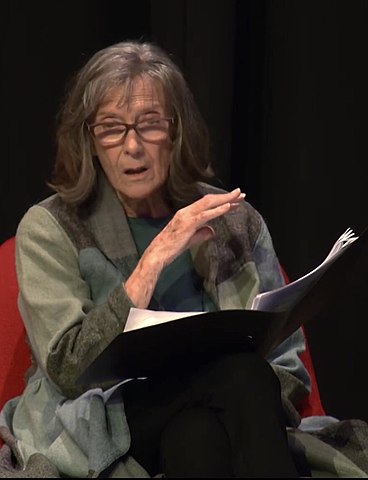

Photo Credit: Dame Eileen Atkins, co-creator of Upstairs, Downstairs, reciting poetry at the British Library, 7 October 2021, The Josephine Hart American Poets Hour: Starkinson/ Wikimedia Commons/ CC BY 3.0

The British TV series Upstairs, Downstairs was the brain-child of two veteran British actresses: Jean Marsh and Dame Eileen Atkins. The two women were dismayed when they watched an earlier British drama The Forsyte Saga (from 1967, not the 2002 mini-series), and realized the series never portrayed the life of the servants who played such a major role in the Forsyte family members’ lives. They wanted to make a comic series set during a time when the class hierarchy was still pronounced in Britain about the troubles and turmoils of those who worked for these aristocratic families – the “downstairs”.

However, when the series was sold, the production company that bought it changed a few things. First, they decided the series should portray not just the downstairs but also the “upstairs,” or, the aristocratic family for which the servants in the series worked (the Bellamys). Second, they decided to take the comedy out of the series and make it more of a drama along the lines of The Forsyte Saga, which had aired four years before the launch of Upstairs, Downstairs in 1971.

One of the fascinating things about this series is that you see how life in the early 20th century (the series ends in 1930) wasn’t easy for either masters and mistresses or servants. Aside from the modern conveniences both had to do without (even though the Bellamys were wealthy so money was no object), the social expectations for both were sometimes difficult to manage.

The pilot episode shows this beautifully, though more from the “downstairs” point of view. Right from the first scene, we see a young woman (played by Pauline Collins) who comes to the house to interview for a position as a maid make the social faux pas of the century — she knocks on the front door. The butler Hudson (Gordon Jackson), his expression one of stoic rage, motions for her to descend the stairs and come through the kitchen entrance and then chews her out for not knocking on the proper door. It’s clear the young woman has never worked in service before, something the other servants, even more than the lady of the house, grumble about. In fact, Lady Marjorie Bellamy (Rachel Gurney) is more sympathetic to the nervous young lady — until it comes to her name. The young lady gives her name as Clemence — a rather “uppity” French name. Lady Marjorie immediately changes it to Sarah and insists she be called by this name. This was actually not uncommon, as mistresses oftentimes either changed the names of their servants or they simply couldn’t be bothered to remember their name so they called them by the name of a former servant they had become used to.

Sarah ends up leaving service quite early in the series (though she does return later on) because, after getting a taste of not only the physical harsh labor but the social and psychological humiliation as well, insists on something better for herself. Members of the family feel the constraints of their social position as well, though in different ways. We see this with the father (whose background is respectable but whose aristocratic standing comes from his wife, and his Parlament peers never let him forget it), the son (whose military position doesn’t always suit his tastes), and the mother and daughter (both of whom suffocate under the constraints of the separate spheres so heavily cherished, especially in Britain, during this time).

Sometimes research can be really fun, and I was lucky enough to catch this series when it was on Netflix in its entirety. It served me well for my upcoming release, The Case of the Dead Domestic, which involves the death of a lady’s maid and the divide between the wealthy of Arrojo and the working class. The book comes out at the end of this month but feel free to pick up a copy now at a special preorder price here.

If you love fun, engaging mysteries set in the past, you’ll enjoy The Missing Ruby Necklace! It’s available exclusively to newsletter subscribers here. By signing up, you’ll also get news about upcoming releases, fun facts about women’s history, classic true-crime tidbits, and more!