Did you know May is National Mystery Month?

Today, May 4, marks a milestone in American criminal history. On this day in 1931, one of the most ruthless and famous crime bosses of the Prohibition Era, Al Capone, began serving his 11-year prison sentence for tax evasion.

America has always had a bee up its bonnet about liquor and in some ways, still does (I live in a county that was a “dry” county — i.e., no selling liquor within county lines — until 1999). Temperance was high on the list of reforms during the Progressive Era. After World War I, the nation’s government decided to do something about it. So in 1919, the Volstead Act was passed, prohibiting the making and selling of liquor in America. In 1920, the Prohibition Era kicked off in America, bringing with it the birth of the gangster, the speakeasy, and the Tommy gun. It also marked the most violent era in criminal history in America.

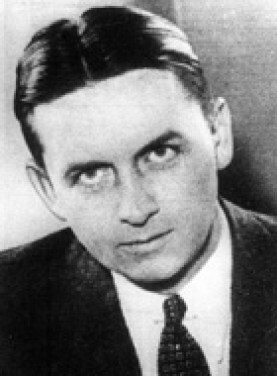

I meant to write this blog post about the criminal (Al Capone). But digging deeper into the history of Prohibition law enforcement, I became more fascinated by the crime fighters than the criminal. Because there was a team of crimefighters that brought down Capone and they were led by one man: Eliot Ness.

Photo Credit: Eliot Ness, 1933, retouched: Melesse/Wikimedia Common/PD US government

Ness worked for the federal government and he and his men had a reputation for being smart, heroic, and incorruptible (no mean feat during this era). He worked for the ATF (Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms) department which put the fight to enforce anti-liquor laws right up his alley. In 1930, his department paired with the U.S. Department of Justice and Treasury in the fight against violent crimes in America which had reached their peak. That year was also Hoover’s declaration of war against the gangsters largely responsible for those crimes. At the head of the list was Al Capone, who had risen to fame as Chicago’s kingpin and evaded every criminal accusation made against him.

The message was clear: get Al Capone on something, anything. Agents worked several angles, including the (obviously) prohibition violation angle and the income tax evasion angle. In the end, the treasury won. Though Ness and his team managed to get enough evidence together to bring forth thousands of prohibition violations against Capone, the kingpin eventually was sent to jail not for the many people he had killed and the violence he and his gang instigated but for avoiding his income taxes.

Why was Capone found guilty of tax evasion rather than prohibition violations (those charges were eventually dropped?) One theory is prosecutors were afraid the jury would find Capone not guilty of the violation charges because, frankly, everybody hated prohibition, and many saw gangsters that fought against it as heroes rather than criminals. Tax evasion, though, was a different matter. Most citizens weren’t sympathetic to those who didn’t pay their taxes (just as we are today). Keep in mind Hoover’s orders: get Al Capone on anything.

Still, Ness made his mark in history. In fact, he was so well known during this era that in that same year, cartoonist Chester Gould created a tough-talking, smart private eye who would become an icon in detective fiction.

Come meet the crime fighters of my Adele Gossling Mysteries, starting with Book 1, The Carnation Murder, which is out now and at 99¢ (though not for much longer!) You can get all the details about the book Barnes & Noble chose for their Top Indie Favorites list here.

If you love fun, engaging mysteries set in the past, sign up for my newsletter to receive a free book, plus news about upcoming releases, fun facts about women’s history and mystery, and more freebies! You can sign up here.