Today is a special day for the people of China as it’s National Day of the Chinese Republic. On this day in 1911, a group of revolutionaries led a revolt against the Qing Dynasty. They overthrew the imperial rule that had dominated for centuries, declaring the country a republic. You can read more about the revolution here.

Why am I mentioning this? First, we are all connected to one another in some way, so knowing about the history of other countries besides our own is part of that connection. Second, I’ve come to appreciate the struggles of the Chinese not only in their own country but in others as well, especially during the early 20th century. In fact, it was researching the 1906 San Francisco Earthquake and the rebuilding that happened afterward for my upcoming book, Murder Among the Rubble, that led me to not only appreciate the way the Chinese were treated during this time but also to include this community in that book.

Photo Credit: Chinatown, Waverly Place at Clay Street, 9 April 1900 (six years before the earthquake), glass plate negative: San Francisco Public Library/Flickr/CC BY NC ND 2.0

San Francisco is known as a liberal city that opens its arms to all and celebrates its diversity. But it wasn’t always this way. Many ethnic groups like the Latino and Asian communities, experienced abominable racism in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Before the earthquake, the Chinese, who numbered about 15,000, were seen as instigators of corruption and vice. They were regulated to a twelve-block radius known as Chinatown and forced to live under squalid conditions. Many couldn’t find decent work and resorted to earning a living with businesses catering to the tourist trade or related to vices, such as opium dens and prostitution houses. The community was stereotyped as one without morals and willing to engage in criminal activity such as the slave trade. This stereotype was so prevalent that a film made in 1965 portraying the Chinese in Chinatown in this way garnished protest from Asian-American actors and led to the creation of the East West Players. I wrote about that here.

When the earthquake hit San Francisco in 1906, Chinatown was, like eighty percent of the city, destroyed. About two-thirds of the Chinese living there fled to Oakland (where they weren’t welcomed – if you can stomach it, read this article that appeared in the Oakland Herald and really shows the attitude toward the Chinese at the time). The other third remained in the city.

Photo Credit: Chinatown after the earthquake, 1906, Harold B. Lee Library: Picryl/Public Domain

The committee that was formed after the earthquake to oversee the rebuilding was faced with what to do with these people. The remaining Chinese were first placed in makeshift tents on Van Ness Avenue, far away from any of the main camp locations, but officials feared they would slowly migrate back to their ruined homes in Chinatown (more about why this was a concern to the committee later). So they were transferred to the Presidio to a separate camp on the other side of the reservation, far away from the main camps populated by Caucasians. Their tents were much smaller, and the food, supplies, and medical attention they received were inferior to those of the whites.

During the rebuilding phase after the earthquake, one of the biggest debates was the question of the fate of Chinatown. Logic would dictate the city would rebuild Chinatown where it had been before, just as they were rebuilding all other neighborhoods in the city. But the real estate of those twelve blocks was prime and businessmen who had been trying to get their hands on it for years saw an opportunity to steal it from the Chinese (since records of their leases would have been burned in the ires). These businessmen tried to get officials to move Chinatown to Hunter’s Point, a remote part of the city used by the Navy shipyard at the time.

Luckily, they did not succeed. The Chinese community in San Francisco, though relatively small, was not without a voice or its supporters. A delegation consisting of American-Chinese and Chinese authorities like the Consul-General of San Francisco called upon the governor to protest against the move, threatening to cut off commercial ties with China. The delegation made the following powerful statement: “America is a free country, and every man has a right to occupy land which he owns provided that he makes no nuisance.”

Photo Credit: Chinatown in San Francisco (in all its glory), taken 2 December 2007 by Tony Webster from Portland, OR: Hiku2/Wikimedia Commons/CC BY 2.0

Moved by this plea (and by the idea of losing trade relations with China), officials nixed the idea of moving Chinatown to Hunter’s Point. Chinatown was rebuilt where it had stood before the earthquake and where it still stands today. The area lost its reputation for vice after the earthquake when the city “cleaned up” such places as the Barbary Coast and Chinatown. Instead, it became a tourist attraction, rebuilt with ornamental gates, panoramas, and pagodas. It’s now one of the most popular places to visit when in San Francisco.

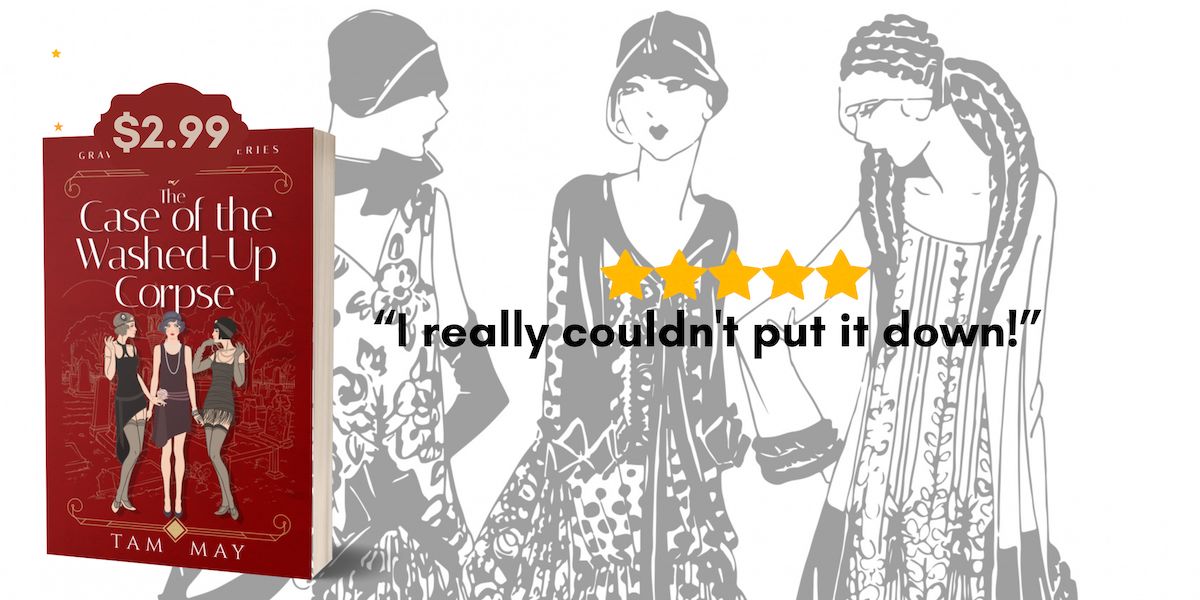

If you want to find out more about how the Chinese faired after the San Francisco earthquake, be sure and check out Murder Among the Rubble, coming out at the end of this year. You can pick up a copy for preorder now at a discount on all online bookstores.

If you love fun, engaging mysteries set in the past, you’ll enjoy The Missing Ruby Necklace! It’s available exclusively to newsletter subscribers here. By signing up, you’ll also get news about upcoming releases, fun facts about women’s history, classic true-crime tidbits, and more!

Works Cited:

“Chinese Make Strong Protest”, San Francisco Chronicle, 30 April 1906. https://sfmuseum.org/chin/4.29.html. Accessed October 4, 2024.